The Cause for Number Systems

Counting With Lines

The simplest possible counting system that we can think of is just drawing lines to represent quantities. That is, to represent number three, we would draw |||.

It is quite clear that, even to represent relatively small numbers, this unary system doesn't work all that well, as illustrated by this representation of number twenty-two:

||||||||||||||||||||||

Note that it takes a pretty long time to read this small quantity. Imagine having to count anything over a hundred by using this system!

Tally Marks

Grouping quantities is an obvious solution to the problem, such as we do when counting score in a game. The unwritten standard says that we group lines by clusters of five, since those are easy to identify at a glance. Thus, number twenty-two would be written as follows:

|||| |||| |||| |||| ||

But this system quickly fails when the number to represent grows just a little bit more. Here's what writing one hundred and seventy-three looks like:

|||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||| |||

Can you tell at a glance whether the count is right?

Roman Numerals

The Romans were also faced with this problem, and decided to tackle it (rather inefficiently) by using lots of symbols for differently sized groups. They also set a bunch of rules according to which a digit would add or subtract its value from the total depending on where it was placed. They got very far with this system, and you can easily represent somewhat big quantities using Roman numerals. For example, here's the number one hundred and seventy-three as Spartacus would have written it:

CLXXIII

However, the Roman system also had its limitations. Among other problems, a particularly annoying one is that numbers larger than three thousand, nine hundred and ninety-nine simply can not be written. There were many extensions to the system to circumvent this issue, but none of them were standardized.

This in itself was a problem, but even if one of these extensions had been adopted by the whole empire it wouldn't have solved other problems like the difficulty of carrying out relatively simple mathematical operations like adding, subtracting, multiplying or dividing two numbers.

The Hindu-Arabic Numeral System

The Hindus had two brilliant ideas. The first one was to assign different values to the same symbol depending on its position, thus never running out of symbols while still making pretty substantial quantities recognizable at a glance. The second brilliant idea was to have one of these symbols represent the quantity zero, thus opening the door for complex calculations.

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system that we commonly use today consists of the ten digits ranging from 0 to 9. Let's investigate how we combine digits in the Arabic numeral system to form arbitrarily big numbers out of just ten symbols.

Counting up to nine is trivial, as we just need to write the digit that corresponds to the number (0 for zero, 1 for one, 2 for two…). Once we reach 9 and want to count one more, we use a digit 1 to represent how many groups of ten units we have, and a digit 0 to represent how many groups of one unit we have.

In other words, 10 means 1 group of ten, plus 0 groups of one.

This goes on forever. Representing three hundred and forty-two, is done by combining the digits 3, 2, and 4, and means:

3 groups of a hundred, plus 2 groups of ten, plus 0 groups of one.

This system is said to be a positional base-10 system, since it has ten symbols and their actual value depends on their position. That is, the digit 5 can mean five if it is in the units position, but it can also mean fifty if it is in the position of the groups of ten, or even 5 millions if it is in the seventh position from the right.

Maya Numerals

The Mayans also had the same two brilliant ideas a bunch of centuries earlier, but with a little twist. While the Hindus used ten digits, presumably because they were basing them on the number of fingers in our hands, the Mayans used twenty digits instead.

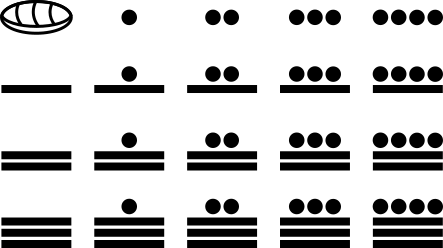

Let us take a look at these digits:

The first digit at the top left of the grid represents zero. Presumably, it depicts some sort of an empty shell. To its right, we find increasing digits from one to four. After four, we use a horizontal line to represent one group of five, and then keep adding dots to it to represent six, seven, eight and nine.

Two horizontal lines make for two groups of five, that is, ten, after which we keep adding dots.

This goes on until digit nineteen.

If we wanted to represent twenty, we would have to use digit one to represent a single group of twenties, and a digit zero to represent zero groups of ones, like this:

.

.

Just like in the Hindu-Arabic system positions accounted for exponentially bigger groups of ten (1, 10, 100, 1000…), in Maya numerals they account for exponentially bigger groups of twenty (1, 20, 400, 8000…).

To represent, say, a hundred, we'd do five groups of twenty, and zero groups of one, that is:

.

.

Here's how to write a bunch of numbers in Maya numerals:

| Quantity | Maya | Hindu-Arabic |

|---|---|---|

| thirteen |  |

13 |

| twenty |   |

20 |

| thirty-six |   |

36 |

| one hundred |   |

100 |

| two-thousand and twenty-two |    |

2022 |

Students can now try to dissect these quantities in their respective groups of units, groups of twenties and groups of four-hundreds, and also try to write arbitrary quantities in the Maya system, like their day, month and year of birth.

What would addition and subtraction look like using this system?

Other Systems

Your students could try to make up their own number system based on different amounts of symbols. For example, make up a number system that only has four digits (for example +,-,x,o), or maybe even a number system with only two digits (for example o and x.)

You can encourage them to be creative with their digit symbols and use made up glyphs. Using symbols different than the ones in the Hindu-Arabic system will help abstract away the notion of a numeric system.

Have your students try to guess the values of randomly written numbers in these systems that they've made up, and have them try to come up with a way to represent any quantity in these systems.

Is having a digit representing zero a requisite? What happens if they don't have a zero digit?